Introduction

Introduction: the early influences

While he studied the internal workings of his opponents

in order to fight them effectively; they clearly did not do the same.

John Saxon’s mother said after his birth in 1923—this being her first born—that she didn’t think she wanted another child. At her age of 30, she said he just “wore her out.” He was a demanding presence from birth—very active, difficult to manage, and hard to discipline. He wasn’t defiant, just determined to do what he wanted.1 He was, from the start, fully engaged in life—going forward in every direction. Any voice or directive that interfered with his activities was to be ignored. John later refined that behavior into “adventuring” as he taught his four children to experience all of life’s events as fully as possible—especially the non-material ones. And even though his mother didn’t plan on having another child, a baby sister, Anne, arrived two months before John’s fourth birthday.

John continued to push boundaries throughout his 72 years which included three distinct careers. In his first one, he finally learned to channel his boundless energy due to the regulated structure he had to follow at the United States Military Academy at West Point, but he was able to fulfill his need for bold activity over the next 21 years as a combat pilot in the Korean War, an Air Force test pilot, and a year in Vietnam. After teaching engineering at the U.S. Air Force Academy for five years before being sent to Vietnam, John retired from the military in 1970 as a lieutenant colonel. After settling his family in Norman, Oklahoma, he followed what seemed to be a natural progression into teaching mathematics part time in a junior college. This became his second career for the next 15 years. His third and overlapping career to his teaching duties was his becoming a mathematics textbook author and publisher.

**********

John Harold Saxon, Jr., born Dec. 10, 1923, in Moultrie, Georgia, came from a family of teachers, physicians, farmers, and “contributors.”2 His mother, Zollie McArthur Saxon was called “Mimmy” (pronounced like “Timmy”) by her children and was a graduate of Agnes Scott College, a Presbyterian-affiliated liberal arts school for women in Atlanta. She had been a teacher for several years before marrying John’s father and later taught her son a firm grasp of Latin as well as a love for reading.

His father was graduated from Oxford College at Emory University and earned a master’s degree from Mercer University. Called Harold, he had been a teacher, principal, superintendent, State High School Supervisor for Georgia, Secretary of the Georgia Accrediting Commission, and then Executive Secretary of the Georgia Education Association until his death in 1956.

John was a descendant of Daniel and Jennet McArthur, who arrived from Scotland in 1744 to settle in North Carolina. Daniel served in the North Carolina regiments during the Revolutionary War, after which one of his children, John, and his wife Harriet moved to Georgia around 1814. There, he became a prosperous farmer. His son Daniel was a licensed physician and practicing dentist. Daniel had 11 children, one of whom was John Saxon’s maternal grandfather, Charles Zollicoffer McArthur, an 1899 graduate of the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Atlanta. He practiced dentistry until ill health “compelled him to retire” and he started farming peaches and pecans.3

John’s paternal family members were also early settlers in the new colonies, starting in 1698 in Virginia with Samuel Saxon. As an adult, Samuel moved to North Carolina, where he died in 1766. The Saxon family then moved to South Carolina. Two of the men served as captains in the South Carolina Militia during the Revolutionary War and his great-grandfather later served as a colonel in the Confederate States of America. His grandparents had four children, three girls and a boy, and one of those girls would prove to be a particular blessing to her only brother, John’s father.

That special sister, Lizzabel Saxon, who died at age 102 in 1990, “had benefited from a Methodist evangelist, Dr. Sam Jones, who saw that she had an unusual ability and asked to be her benefactor as she pursued her education.”4 She was graduated magna cum laude from Agnes Scott College. Its website today describes the continuing purpose of the school, founded in 1889, as being one “to educate women to think deeply, live honorably and engage the intellectual and social challenges of their times.” She was presented with scholarships each year for the “highest grade accomplishments.” Lizzabel received her master’s degree from Columbia University and taught foreign language and mathematics in Atlanta area schools until 1953. It was “Auntiebelle” who ensured that her brother and sisters could attend college if they chose to do so with her financial and emotional support. Because of her, John’s father was given the opportunity to become a teacher and administrator.

The educator’s tradition extended into John’s marriage as his wife, Mary Esther, became a university librarian later in their marriage. This continued her family’s respected history within education. Mary Esther’s mother had been a teacher and her father, D. Bruce Selby, was the Enid, Oklahoma, high school principal from 1939 to 1954. Much beloved by the whole community, Mr. Selby’s funeral was the largest ever seen in the city when he died in 1968. John’s daughter, Selby, said that when her grandfather died, she remembered her dad wept for days. “He said my grandfather was the kindest man he had ever met. It’s the first time I saw Daddy cry like that.”5

John thus had a rich history of educated family members with teachers among them, as well as a powerful education of his own making. However, a strong Georgian accent, while charming to many, was said to have contributed to the discriminatory caricature among some elitists toward Southerners, as pointed out by the new CEO of his company in 2002.6 Such people couldn’t know and evidently didn’t care to learn that John had witnessed what good teaching and learning was all about from his mother and what politicking within the insular world of public education was all about from his father.

He also absorbed a lifelong lesson from Auntibelle who loved both mathematics and foreign languages, as well as helping others in her family and community. That is, because of his family’s rich diversity of interests and studies, John actually embodied the philosophy of “integrated” learning from the “real world” so promoted by his opponents. His son Johnny says his father was a true Renaissance man because he truly loved history, good literature (poetry, especially), and foreign languages. The mathematics needed in his career became a valuable tool that helped him enjoy all those other areas of life.

**********

It was this background—a innate drive to experience life to the fullest, a joy for learning and teaching and giving to others (which was further instilled with the West Point motto of “duty, honor, and country”), and being deeply moved by truly special educators—that drove John Saxon into battle against the disastrous condition of mathematics education in America. He learned to distrust and, more, to despise a blind allegiance to ideology rather than to providing positive results to children.

While he studied the internal workings of his opponents in order to fight them effectively, they clearly did not do the same. They thought if they just ignored this “military man” who had invaded their territory, he would go away. This cost them, professionally. Their reactions to him and his program showed them to be false practitioners of tolerance, diversity, and creative thinking toward any individual who would not follow their ideology without question. It also cost them financially. By the time John’s company was purchased in 2004 by a major publisher, eight years after his death, it had sold seven million books throughout 100 countries.

John Saxon had proven a mathematics textbook did not have to be a clone of those that came before it. He was indeed, as Johnny said, a Renaissance man who saw the bigger picture of what students needed for a lifetime of achievement and, at the same time, was willing to be a strong warrior for just causes.

That warrior mentality would be the one John Saxon called upon, surprising his opponents with a vigor and determination they had not witnessed before in America’s world of mathematics education.

End of Introduction

Quotes from supporters

John Saxon wrote a masterful mathematics program, but his "Saxonisms" could and should apply to every classroom in America. By skillfully revealing the genius of John Saxon, Niki Hayes, an experienced educator herself, has produced a practical teachers' manual for both new and experienced teachers.

Here is Saxon at his very best: "A firm footing in the fundamentals prepares them to handle the theoretical for all disciplines...Students who practice diagramming sentences and who write numerous essays, book reports, and stories are better equipped to debate literature. Students who memorize names and dates and speeches and documents are better equipped to debate history."

Donna Garner,

Retired English teacher

and education activist

Hewitt, TX

As an elementary teacher with a math degree, I have always created my own curriculum for math while pulling from multiple resources. Saxon is the first curriculum that I have used to its entirety because it is a turn key comprehensive textbook. The weekly diagnostic test is especially important because it provides immediate feedback for clarification and remediation. The level of confidence and proficiency received by students using Saxon Mathematics speaks highly for the program.

Linh-Co Nguyen,

Elementary math teacher

Seattle, WA

John Saxon was the 'George Patton' in the Math Wars with his frontal attack against the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics and the failed belief system they put on mathematics instruction.

Jimmy Kilpatrick,

Editor, EducationNews.org

John Saxon was a visionary. He believed that students could more readily master math concepts through daily review, rather than by just memorizing them for a good test grade. Having taught high school mathematics using John’s math books for more than a decade, I can assure you that is exactly what happened in my math classes. Our ACT math scores exceeded the national average for years and we had more than 98 percent of our students enrolled in the more advanced math classes.

Art Reed,

Retired high school Saxon Math teacher and author, Using John Saxon’s Math Books—How Homeschool Parents Can Successfully Use Them and Save Money!

From the author…

Dedicated to my parents, Harold and Sara Smith, common sense folks who modeled good teaching, and to my Kansas cousin Jeananne Blakely, who gives unceasing support for my efforts.

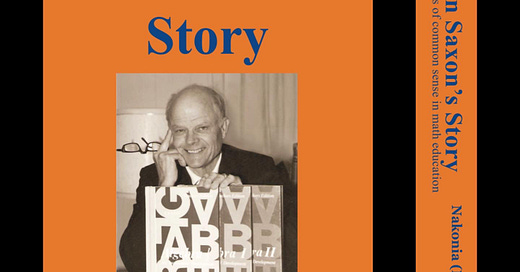

John Saxon initiated a profound and positive impact on American mathematics education in 1981. His story, after fifteen months of research and interviews, evolved into far more than a two-dimensional portrait of this colorful teacher and author who died in 1996. For one thing, the incredible establishment of Saxon Publishers, an entrepreneurial venture that had little expectation of succeeding according to the math establishment leadership, had to be told. The content of his revolutionary new program, on which that publishing house was built into a multi-million dollar enterprise, became another important element in the story.

Since his math series is still highly rated by those who use it today, it seemed appropriate that a user-friendly “teaching” almanac be included in the book. It would explain the correct way to use his program, mostly in John’s own words.

Finally, for total clarity of the whole John Saxon story, an up-to-date review had to show whether or not his constant, irritating demands on the mathematics establishment leadership—that have made them despise him even to this day—were warranted.

In fact, they were. John’s unique design for successful mathematics programs for kindergarten through the twelfth grade has been confirmed by respected individuals of academic stature and reputation. To him, his math program was nothing more than common sense.

John Saxon’s Story thus turned into a comprehensive history of a rare man who showed a genius for using equally rare common sense in the world of mathematics education. It is hoped that the thoroughness but the clarity of this story would have pleased him.

Nakonia (Niki) Hayes

Saxonisms*Results, not methodology, should be the basis of curriculum decisions.*Creativity springs unsolicited from a well prepared mind.*Mathematics is an individual sport and is not a team sport.*Students do not detest work; they detest effort without purpose.

*Beautiful explanations do not lead to understanding.

*Saxon books will win every contest by an order of magnitude.

*Teachers are not paid to teach. Teachers are paid to find a way for students to learn. You do not teach mathematics with your head, but with your heart.

*Making eyes sparkle does not come from erudite mathematics.

*Teachers say they are going to teach the children to think. The children can think already. What they need to know is the math to use in their thinking.

*Dr. Benjamin Bloom says you must overlearn beyond mastery until you can do it like Fred Astaire said: “Do the dance while reading Shakespeare.”

*I contend that our job is to teach rewarding responses to mathematical stimuli, to teach thought patterns that have been found to lead to the solutions, to allow the students to practice reacting to the stimuli with these thought patterns and to be rewarded with the warm feeling of pride that accompanies the correct answer.

*I believe that students should be gently led and constantly applauded for their efforts.

*I oppose intimidation in any form. Mathematics classes can become warm sanctuaries towards which students gravitate because there they are asked to solve puzzles by using familiar thought patterns.

*Most math books are like the Book of Revelation—horror stories and surprises from beginning to end. Students see my book as the 23rd Psalm. It’s a nice safe place to go.

*You grasp an abstraction almost by osmosis through long-term exposure.

*You can’t put your hand on it. That’s the reason we call it an abstraction.

*We’ve never had research that shows how long it takes for students to absorb abstractions in mathematics. It takes a long time. Then the summer lets them forget it.

*Meaningful education research is an oxymoron. We have more education research in America than all the other countries and kids are at the bottom.

*The math educators spend time at the universities playing like their scientists and they publish their papers.

*If it were possible to teach people to think, it would be possible to teach professors of mathematics education to be mathematicians. The only difference between a mathematician and a professor of mathematics education is the creative spark.

*We have allowed this fraud, this pasquinade, on education by these people who are literal and total gross incompetents, and they have destroyed mathematics education in America to the point that I, a retired Air Force test pilot who has flown two combat tours, and whose profession was killing, know more about teaching than they do.

*It has to stop right here, right now.

*The time for inactive skepticism is past.

*I’m going to bypass the math establishment because a man convinced against his will is of the same opinion. I will run over these people with a bulldozer.

*Either I am the most brilliant thing to come down the pike, having doubled some students’ test scores, or the people in charge of math texts are totally incompetent.

*This is more than one man lighting a candle. When they see the brilliance of this candle, they’re going to have to light their own or be overpowered.

*I know I don’t make headway by speaking out this way, but I am determined to change this system of math education.

*Our math experts aren’t really experts; they have abdicated all claim to control by their behavior of the last 20 years.

*I’m mad, and I’m doing something about it!

Share this post