Chapter 5: a crash, soaring heights, then personal devastation

“God bless your heart; you’re a mighty brave lady.”

John to his rescuer

For the fourth time, John experienced another airplane crash but this one nearly killed him. He was a B-25 instructor pilot on a routine training mission with another pilot, Capt. Pete Peterson, on Aug. 21, 1953. Just as they flew over a fence line on takeoff near Wright Patterson AFB, the airplane started flying sideways. The nose went to the right and John hollered, “I got it.” The pilots had a nine-step single engine procedure and, John said, “It’s amazing what you’ll do if you’ve automated these things.”

He started the procedures but they needed about 145 miles per hour and they only had 118. The effectiveness of the rudder depended on airspeed. The plane was out of control; the left engine caught on fire. John said there was nothing but trees and houses and no where to set the airplane down with their wing load, so he called in saying, “1199 going in…” The good engine was pulled off as they hit the ground in front of an embankment. The airplane went up, crumpled, and went through some trees, spewing out into a field. “When we hit the ground, my right hand went forward into the instrument panel. That’s how my fingers got broken.” The cockpit rolled and ground up to where John was.

John remembers it was a beautiful August morning—and he could hear fire burning. He got his straps loose but couldn’t get his left hand free. He put his feet up against something and forced his hand loose. “I really thought I would have to pull off my finger because his wedding band was caught.” He passed out from the pain. The next thing he knew, someone was grabbing at him. He said, “Fellow, you got your hands full!” He was so tired. He figured the fellow would have to pull his feet out of his shoes because his feet were caught. Whoever it was got him under the arms, yanked him out of the plane, and started standing him up. It was a woman in shorts and a halter top. “She was covered with blood,” he said. “She looked like she had been to a pig sticking.”

The woman asked if anyone else were in the plane and he told about Pete. John was going in and out of consciousness, but all of a sudden there were three men and a young woman trying to get Pete’s seat free. John reached under Pete’s seat but the lever was stuck. They started beating the canopy with rocks and then they found a fire extinguisher to break an opening into the canopy. Pete was pulled out; they had all moved about 150 feet from the airplane when it exploded into a ball of fire. There were three explosions altogether.

The woman, named Genevieve Zimmerman, was a 40-year-old farmer’s wife who weighed 130 pounds. Her 18-year-old daughter, Darlene, had been helped by Vernon Wheeler, an operator of a nearby gravel pit; Marion Miller, a farmer; and Dan Warner, another neighbor, as they pried open the wreckage and all pulled together to release Pete. Darlene had called the fire department prior to running to the site and helping her mother.

John said the woman took them to her house and he knew he couldn’t sit down because he needed the adrenalin to keep from passing out. In Mrs. Zimmerman’s newspaper interview, however, she said John gave her a lot of trouble. “He wouldn’t stand still,” she said. He called military officials from her house and then called Mary Esther. He told her he’d been in an accident but that she didn’t need to come to him because everything was fine. He remembers walking out of the house and a woman who had come to see what was happening started screaming at him like he was a monster. John later realized he was covered in blood that was dripping from his head and hands, as well as being caked in dirt from falling on the ground. He must have been, he said, a frightful sight.

He headed toward the road and a policeman said he couldn’t help John because he was directing traffic. Of course emergency vehicles were on the way, but John wanted someone to take him to the hospital right then. John remembers giving him some “choice words.” Then he started across a field and was trying to climb over a wire fence to get to the helicopter that had arrived. “A guy on the other side of the fence kept telling me to sit down and I kept yelling for him to help me across the fence.”

John said, “I had been trying for months to get a ride in that helicopter, so I was going to get over that fence and get in it.” He did just that. The ambulance, meanwhile, was picking up Pete. That helicopter’s landing on the volleyball field behind the hospital was the first such direct “air ambulance” service that Air Force officials could recall. They had an ambulance then take John to the emergency room where, he said, he was screaming from the pain but they wouldn’t give him any medication because of his head wound. John asked the doctor if he were going to give him a “general” and the nurse with an intravenous syringe said, “You’ll never see the plunger hit the bottom.” He didn’t.

John said while he was in the operating room, “The idiot who wouldn’t help me over the fence called Mary Esther and told her that I had a bad hand wound.” When he realized she was waiting to see him, he put a towel over his hands so she wouldn’t see the extent of his injuries. What he didn’t recognize was that his head was fully bandaged and covered with 40 stitches. To his surprise, Mary Esther was composed and simply asked if he were okay.

The following day, John and Pete met with Mrs. Zimmerman and Darlene in the hospital. “God bless your heart; you’re a mighty brave lady,” was John’s smiling comment from his hospital room. A photo of John and Pete talking with the two women appeared in the local newspaper, along with pictures of the crash. Another highlight of that following day was the return of John’s wedding ring which had been found in the debris.

Life around the farmer’s wife was followed for a few days in the local newspapers as more interest turned to her and her bravery. She told reporters she had only one regret: When she heard the airplane going down, she had been painting the floor of her back porch. “The people rushing in and out of the house stepped on the new paint, so now I’ve got to do it all over again.” After that news story, two young lieutenants showed up at her house and offered to repaint her porch. They said, “The two captains called and said they had heard about your back porch being messed up. Any painting you need done, we’ll do it. We like those pilots and we can’t express enough thanks for what you did.”

Base officials blamed the accident on the failure of the plane’s left engine shortly after it took off from the field. High ranking officers who examined the wrecked aircraft said the rescue was miraculous. They said if military personnel had taken part in the rescue they would have been eligible to receive the Soldier’s Medal, the armed services highest award for heroic deeds not involving combat. As a civilian hero, Mrs. Zimmerman said one woman had given her a case of beer and said, “Medals are a long time in coming; this’ll do you some good now.”

John remained in the hospital about 10 days but checked out early in order to be ready for his September classes in aeronautical engineering. The rest of the story about this time in his life was told simply as, “I studied about 30-35 hours a week and we lived a reasonably normal life.”

At the end of that year at the Air Force Institute of Technology, John had a second bachelor’s degree in engineering added to his first one from West Point. It was 1954.

This additional education eventually set him up to be accepted in the U.S. Air Force Aerospace Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, California, where he was graduated in 1957. He was assigned as an aeronautical engineer and test pilot in the Performance Engineering Branch of the Flight Test Division for the next five years, during which time he flew experimental fighter aircraft. John often expressed great pride for having worked with Gus Grissom and Gordon Cooper, both of whom later made history as astronauts with the National Aeronautic and Space Administration (NASA). John had also applied for the first astronauts’ group training but learned he was an inch too tall. For the second group, he was a year too old.

His age became a determining factor in his career once again, in that he was required to leave his test pilot position. At that point, he decided to attend the University of Oklahoma to earn a master’s degree in electrical engineering on a temporary duty assignment. In 1963, with a third engineering degree in hand, John was hired to teach at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Five years later, in 1968, he was ordered to duty as a pilot in the Vietnam War.

Assigned to Eglin AFB in Florida in 1969 after his stint in Vietnam, he was a lieutenant colonel. He had been passed over for promotion and this would force him to retire. Such administrative decisions could have come for a variety of reasons but it was a common one during those particular years in order to achieve the “RIF” (reduction in force) that had been mandated with the winding down of the Vietnam War. It could also have been that John had crossed someone and a grudge was being held. It was all speculation. Whatever the cause, facing retirement brought on a terrible period for John. He had truly loved the military and his work.

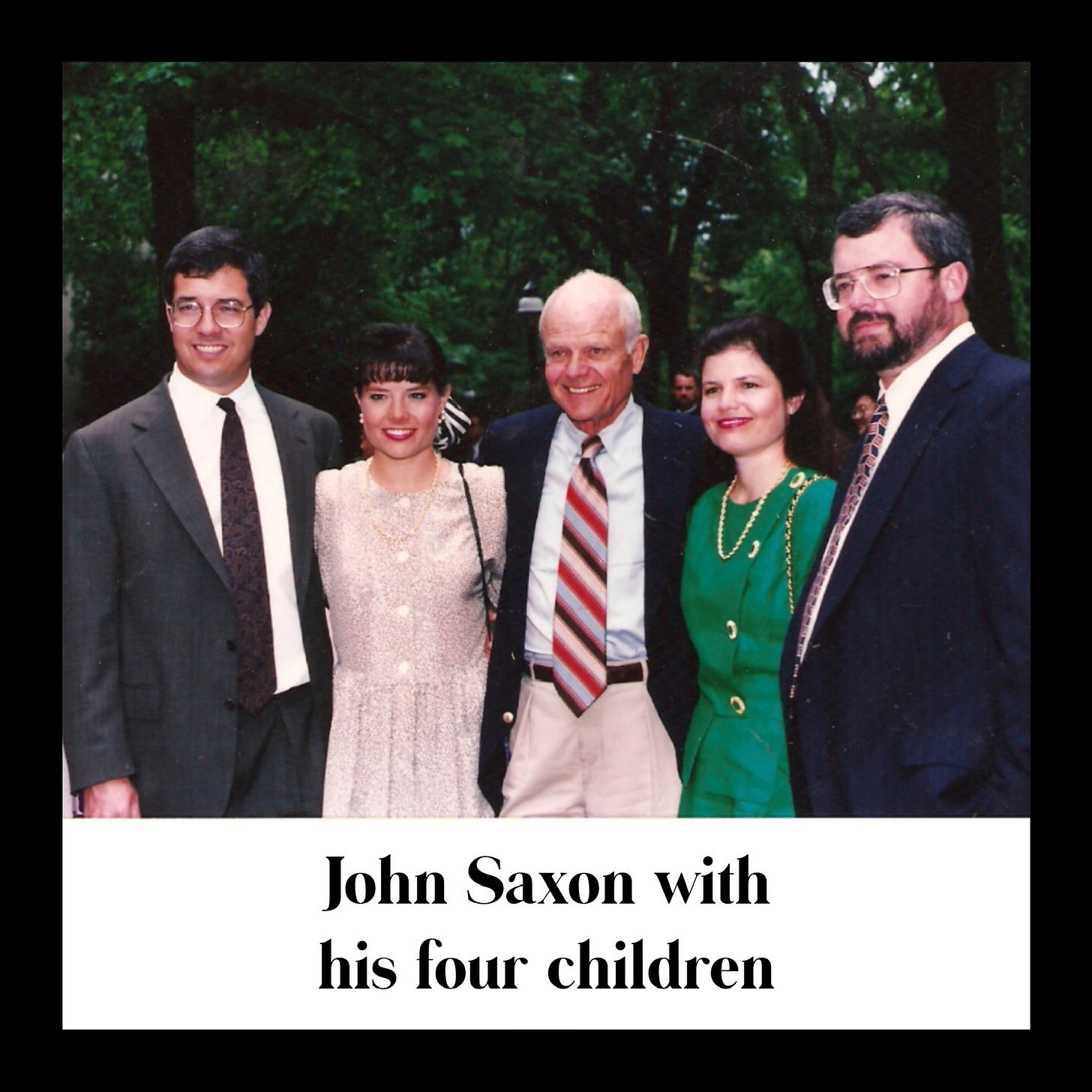

He filed his retirement papers in 1970. Not only was he facing the loss of a beloved career, but his marriage was in serious trouble. He was the father of four children by this time and he feared they would be caught in the middle of his professional and personal crises.

The signs of strain on the marriage had started becoming clear around 1964, perhaps only slightly to John and the children, when he was teaching at the Air Force Academy.

One morning at breakfast that year, after John had left for work, Mary Esther announced to the children that she and they were “going to live with grandma in Oklahoma” and that “Daddy can come see us whenever he wants.” At this time, their fourth child, Sarah, was only a year old. Selby, her big sister at age nine, thought the move would be great because “Grandmother makes cherry pie and fried chicken.”

It didn’t mean anything to her since she was too young to understand fully what was happening—but her older brother Johnny did understand and he told his dad what his mother had said. John went to school that day and pulled Johnny, Selby, and Bruce from their classes. When he got them into the back seat of the car, with Mary Esther sitting in the front seat, he had her turn around and tell them that they weren’t going anywhere.

The marital strain remained through the subsequent six years prior to John’s unwanted retirement.

Share this post